Note: Mark D. Sloss, Chief Executive of Regenerative Investment Strategies, examines our tools of intentionality from our state-of-the-industry report, “Tipping Points 2016”. This article originally appeared in CityWire USA magazine on January 19, 2017.

Note: Mark D. Sloss, Chief Executive of Regenerative Investment Strategies, examines our tools of intentionality from our state-of-the-industry report, “Tipping Points 2016”. This article originally appeared in CityWire USA magazine on January 19, 2017.

———

By Mark D. Sloss

Two columns ago I explored the matter of intentionality, a term borrowed from the impact investing space, in describing the environmental, social and governance (ESG) attributes of an investment strategy.

The Global Impact Investing Network uses it in describing ‘investments made into companies, organizations and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.’

In my column I rented the notion of intentionality to describe public market portfolios deliberately constructed with the inclusion of social and environmental factors alongside financial ratios and traditional business analysis.

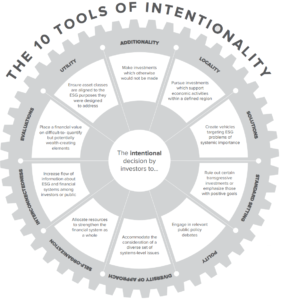

The question on the table now is one of how to actually evaluate intentionality in an investment process. The Investment Integration Project (TIIP) just released their latest report, ‘Tipping Points 2016’, a systems-level study of asset owners and managers in the sustainable investment space. Section two of that report is entitled ‘The 10 Tools of Intentionality’. It was a holiday miracle. This column was going to unpack how to identify and assess intentionality, and the elves came in, did my homework, and polished my shoes on their way out.

I therefore spoke to two of the lead architects of the study, Steve Lydenberg and Bill Burckart, on how these tools are utilized in portfolio construction with my own intention to repurpose them for process and portfolio analysis.

Deconstructing ESG

We started with Adam Smith and the role of an invisible hand in the market. We examined economic efficiency, about which Lydenberg said: ‘If you are driven by efficiency alone (maximizing your return) there are some things you won’t do. You won’t look out for the greater public good because society’s assumption is efficiency in and of itself is a sufficient good. If you want to create social and environmental goods that don’t just relate to risk in the portfolio, that aren’t just going to be reflected in efficient price discovery, that aren’t just accidental, you have to intend to do it.’

Delving more deeply, two of the 10 tools stood out as particularly useful as evaluative ways of looking at ESG managers…..